Overview:

Reading time: 10 minutes

Content warnings:

- Mentions of Mental Health Challenges: Discussion of addiction, body dysmorphia, and eating disorders.

- Reference to Socioeconomic Inequalities: Touches on systemic inequities in wealth and privilege.

- Critique of Copyright and Privacy Norms: May challenge deeply held beliefs about these systems.

- Use of the Term “Stealing”: In discussing sampling, remixing, and AI-generated content, which may provoke strong reactions.

Content Summary: “This blog post explores the author’s personal biases, privilege, and positionality as they begin a research project on AI, accessibility, and the arts, questioning systems like copyright, privacy, and capitalism.” Summary generated by chatGPT 4o.

As I dig into this research project on AI and accessibility, it feels important to stop and ask: where am I starting from? What do I already believe, and how might that shape how I approach this work? What assumptions do I hold, and what biases do I need to check along the way? I have some pretty formed opinions that I need to shelf as I do this work, especially in the early days.

To Read:

- chatGPT and Generative Artifical Intelligence (AI): Potential for bias based on prompt (subject guide), University of Waterloo, Nov 15, 2024

- Shedding light on AI bias with real world examples, IBM Data and AI Team, no date.

Here’s the thing: I am not really afraid of AI. Not in the way a lot of artists I meet are. I have a lot of privilege as a white Canadian citizen and I also have been a bit of a digital cowboy (with all its colonial implications) for the past 2 decades. Because of that, I have come to be critical of one of them major structures AI is accused of threatening in the arts—copyright, or more specifically profit, ownership. Hot take: In my opinion, copyright is flawed, potentially harmful, and in need of an overhaul. It privileges those who already have power, locks down information, and creates barriers to access. The systems it supports, capitalism, profit-driven industries, and even the arts sector—don’t always align with the equity and inclusion we say we are striving for.

And then there’s privacy. A lot of artists express fear about AI related to data theft—concerns that their work will be “stolen,” scraped, or misused without their consent. These fears are real, but they often sit alongside a striking lack of personal accountability when it comes to how we engage with data every day. Many artists (and organizations) are quick to criticize AI but slow to address how they already share and compromise their own data (or causally steal the content of others). Social media oversharing or filming of live performances. Weak passwords. No defensive digital strategies. No clear policies for sharing or protecting data in artist-run or small cultural centres. Using personal phones for work. Phishing attacks often succeed simply because no one took the time to learn how to spot them (which baffles me since this has been a tactic since before the 90s). The responsibility is on us and our employers to do better because regulation and protection from the government runs slowly – and even when it does, it’s federal law first. In Canada, “we” have been trying to get a Digital Privacy Act (C-27) in place since 202X (and before) to attempt to protect how personal information is used – but that process was recently paused again because of how Artificial Intelligence has been tacked on and weird anti-privacy amendment – not to mention a lack of consultation with Indigenous peoples (to oversimplify).

To read:

- Canada’s lack of AI framework ‘a bit embarrassing,’ Champagne says, Mathieu Dion, September 27 2024

- Bill C-27 Timeline of Developments, Wendy J. Wagner, Antoine Guilmain, Michael Walsh, November 2024

- Bill C-27: The Digital Charter Act, 2023 and First Nations Rights (PDF), Assembly of First Nations, October 2023

I don’t bring this up to point fingers. I bring it up because it’s hard to reconcile these gaps in knowledge or care with the level of anxiety around AI, while we literally use and employ these tools ourselves. If privacy and protection are the goals, then where’s the follow-through across all digital use? Where are these people in discussions around data policy and why the heck are we still using our personal phones at work? If privacy and protection are truly our goals, then we have to start by addressing the ways we already fail to safeguard our own work and data. Demanding ethical tools and policies is important, but it means little if we’re unwilling to reflect on our own practices and do the work of care ourselves.

Does this mean I don’t care about artists’ incomes or livelihoods? Of course not—not at all. Like anyone else, I want stability and safety. I want to pay my rent, feed my family, and do meaningful work. Do I want authors to give their stories away for free, and for us to continue perpetuating the ideas that creative practices are less valuable than white collar “professional” or “service-based” ones? Absolutely not. But wealth is distributed unevenly and the drive to “protect” income or intellectual property often reinforces those inequities. For me, this is where care comes in. I care about the ways we survive, collaborate, and create. But care is complicated. It’s hard to reconcile that care with the contradictions I see in how we, as artists, engage with issues like privacy, copyright, and data security. We fear AI “stealing” our work or violating privacy while often neglecting the privacy risks we’ve already accepted or the best practices we overlook for the sake of our own comfort. And here’s the double bind: many artists (myself included) criticize capitalism while also clinging to it, striving for stability or upward mobility in a system we wish to dismantle. I use my personal devices for work, and I have accepted that I am at risk. These tensions are uncomfortable, but ignoring them only narrows the conversation.

I also know that dismissing the fears of my peers who worry about AI’s impact on their livelihoods won’t lead to meaningful dialogue. That’s not what I want.

This project isn’t about proving a point or winning an argument. It’s about exploring how AI might reduce barriers, examining the systems that create those barriers in the first place, and figuring out what “better” might look like for everyone—not just the people AI is designed to benefit but also the people it might harm.

To read:

- When Modern Technology Meets History – How Museums Are Creating Interactive Experiences, Sally Yoon, February 21, 2023

- Arts and Culture, Creative Commons and NFTs: why it’s going to take more than a unique token to solve the unique problems faced by arts and culture producers, karen darricades, August 9, 2021

So, here is where I am starting: I wanted to name my biases, document my process, and stay open to where this work might take me. I want to acknowledge that conflicting ideas can coexist. And I want to figure out how to hold those ideas in balance while pushing this work forward.

Acknowledging Privilege and Positionality

Before diving deeper into this research, it feels necessary to pause and recognize where I’m starting from—not just ideologically, but personally. Privilege shapes our perspectives in often invisible ways until we take the time to unpack them. If I want to approach this work with honesty and integrity, I need to acknowledge the ways my own privilege informs my thinking, my biases, and the assumptions I might bring into this project.

I am a white, queer, gender non-conforming person living in Canada—a country with significant flaws but one that provides me with certain rights and protections. I am ambulatory, sighted, and hard of hearing, but I don’t face barriers that many d/Deaf and d/Disabled people experience daily. I have access to stable housing, clean water, high-speed internet, and healthcare. I can vote, hold a passport, and move freely without fear for my safety. I have access to medication, support for my mental health, and the ability to navigate systems that often exclude others. I am employed, educated, and capable of self-advocacy.

I have been an early tech adapter much of my life with access to tech due to my father’s work, and because I have been hungry for it. From hours spent at my local public library when they first hooked up their computers to phone lines in the 80s to the dreams spurred on my love of speculative fiction, I have been dreaming digital futures since I was a preteen.

At the same time, I know that not all of my identities come with privilege. I have struggled with addiction, mental illness, body dysmorphia and eating disorders. I’ve encountered barriers tied to being non-binary in a society that codes me as femme. And while I am hard of hearing, I occupy a strange space between Deaf and hearing communities, where I don’t fully belong to either.

These privileges and intersections inevitably shape how I engage with AI, accessibility and the arts. They influence how I interpret research, approach conversations, and prioritize certain outcomes. I don’t claim to be without bias. Quite the opposite—I think it’s important to name these biases upfront so that I (and anyone following this research) can stay aware of them as the project progresses.

To read:

- Power, Privilege & Bias, Queens University, Creative Commons Module

By acknowledging my privilege, I’m not looking to diminish the validity of this work or to wallow in guilt. Instead, I want to make space for perspectives that don’t reflect my own experience. Dismantling barriers and creating accessibility doesn’t belong to me alone. It’s collective, requiring listening, learning, and being open to change.

Holding Space for Questions

This post isn’t a manifesto. It’s a very early starting point—a snapshot of where I currently sit as I begin this research in earnest. My opinions may shift. My understanding may deepen. I hope they will. And I hope to keep documenting that process for myself and for anyone following along. For those further along in their processes, I am sure this seems naive and shows the depth of learning still ahead of me. For those just getting started, you’re in good company. We all have to start somewhere.

Technology and transparency

When I finished writing this post, I used Grammarly to check my grammar and spelling (using their English Canada library). I then used readable.com to check whether or not I had adhered to my goals of simple language with this article matching a grade 9 reading level per the Flesch-Kincaid test.

WordPress estimated that my 2,015 word post would take someone 10 minutes to read.

I used chatGTP 4o (plus) to review the entire article, give me writing suggestions for clarity and review for bias/places I needed a source, to create a single-sentence summary, and to suggest content warnings.

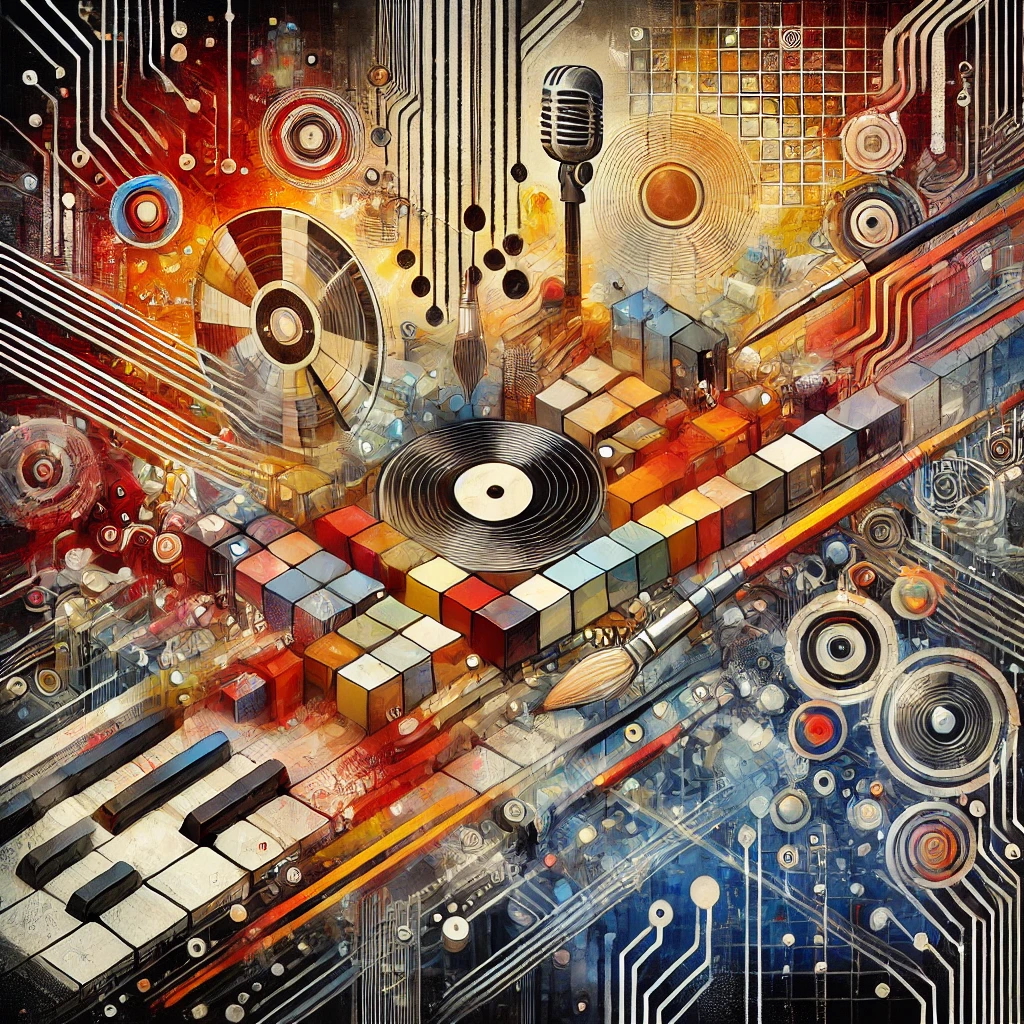

chatGPT generated the feature image based on the draft post text and my query: “make an image that summarizes this post.” I asked it to give me a visual description. Here is the description:

“The image features an abstract composition with bright, overlapping shapes symbolizing artistic tools like paintbrushes, microphones, and vinyl records. These merge seamlessly with fragmented, pixelated grids that represent digital data. Urban textures, reminiscent of graffiti, flow into circuit-like patterns, suggesting a fusion of hip-hop culture and AI innovation. The composition is dynamic, with pathways breaking through barriers, emphasizing the tension between sharing and protection. Warm reds and oranges radiate creative energy, while cooler blues and grays suggest systemic constraints.”

I had originally written about parallels to hip hop and collage, and how data use and remix culture are also a point of interest for me in this, but I cut it for clarity. This content is very apperant and most of the figurative imagery is due to content that is no longer a part of this post. However, I didn’t ask for a new generated image. As much as possible, I want to keep the image generation to once a post unless it’s part of a test.